What I’ve Been Reading

The Hydrogen Sonata by Iain M. Banks

Another excellent romp in the Culture universe. I’m really sad this one will be the last, because they’re all so good. The Culture is one of the most sensible and realistic views of the distant future I’ve encountered in a lifetime of reading SF.

In regards to this story, I’ll just say the ending was not predictable at all, and the Mountains of the Sound is a place I’d love to visit or perhaps even create.

The Black Wheel by A. Merritt and Hannes Bok

I’ve long had the idea of reading all of Merritt’s books, based on the strength of The Metal Monster. This is the third of his books I’ve read, and I have to say it wasn’t terribly great. I didn’t realize until after reading it that more than 2/3 of the chapters were written by Bok, based on a rough outline left by Merritt. I didn’t notice the transition.

It’s a decent enough adventure story with lots of psychological drama, but I had trouble following some of that drama; there were a lot of intuitive leaps that I suspect made sense for the authors’ culture but not for mine. It was good enough to keep me reading until the end, but I wouldn’t recommend it to anyone.

The Apocalypse Codex by Charles Stross

Fourth book in the highly entertaining Laundry series. I was expecting a letdown from reading the back cover copy, as it described the plot as centering around a televangelist type, but this book was very much not a letdown – every bit as engrossing as the previous ones in the series.

I like that Stross is not afraid to involve large pieces of the stage dressing in the action.

Calculating God by Robert J. Sawyer

Mixed feelings about this one. It did provide stuff to think about and had an involving story, but it also felt like the story was made just to be a framework for a guided tour of current thinking in science and cosmology combined with too much conciliation of religious ideas.

Books that are set in places that I’ve lived give me an odd vibe too, but in this case it was better than most – largely because he describes the same trick I always used for getting a seat on the Northbound subway in Toronto.

This one came up in a Facebook thread and the Amazon cover blurb convinced me to read it – it’s good to study your enemies as well as your friends, and their position as represented by Amazon definitely sounds enemy.

Here’s the review I posted in the Facebook thread:

—–

Just finished reading it – it’s short.

In the first two chapters they present a theory that neural firing generates small electromagnetic fields that influence other neurons at a distance, without a direct axon connection, and that in the aggregate these fields are what constitute the meaningful state information in the brain, and encode our mind state in a representation of a Riemann space in which experiences are formed by folding different conceptual and sensory regions together. All of this doesn’t really matter to the important bits though – basically what they’re saying is that brains contain multiple overlapping systems, only one of which (the actual electrical firing of neurons) can be considered digital – the rest are analog.

The rest of the book is a collection of distinct arguments that no digital computer can simulate a brain. For example:

1) Simulating analog phenomena on a digital computer is impossible to do perfectly. While strictly true, I disagree with their assumption that it needs to be done perfectly.

2) It’s impossible to keep all portions of a large-scale simulation synchronized. This is flat-out false; they seem ignorant of basic techniques for keeping simulations stable and synchronized.

3) Brains are special objects. Really, really special. Preciouuussss. Note this is me using a bit of a straw man of my own. They do mention ideas like quantum effects in the brain but don’t go so far as to outright state that brains violate the laws of physics or anything like that.

4) Computers explode in a shower of sparks when you feed them contradictions. No simulation will ever be able to handle contradictory data in a useful way. This is a ridiculous claim to me.

5) Computer simulations are usually created by finding a mathematical representation of a physical phenomenon, then writing an algorithm that solves the math. Even ignoring the analog precision problem from (1), the mathematical representation is often an imperfect representation of reality. This is true of complex systems, but down at the neural level of molecules and electromagnetic fields, I think we’ve got the math down well. Admittedly some of it is probabilistic (ie chance of two protiens bumping into each other) but I don’t see that as a problem.

6) No matter how accurate the computer simulation, it will diverge and fail to perfectly predict the behavior of the organism, because it cannot take into account all the stimuli the organism receives without simulating the entire universe. Well, duh. Also, that’s not a real problem because our senses are pretty limited anyway. And even a perfectly duplicated organism would immediately diverge from itself for the same reason – different sensory input from having a different physical location.

7) If we can’t perfectly predict the original organism, there’s no point in doing this. I completely disagree with this.

8) It is difficult to imagine a simulated brain running in real time, even with more Moore’s Law. If the simulation can’t interact with the world at normal human speed, there’s no point in doing it. Again, this makes absolutely no sense to me.

9) It is difficult to digitally model neuroplasticity – ie the hardware continuously changing while the software still runs. Yes, it is difficult, but not impossible.

Also, the authors seem to conflate simulation with emulation. They’re attacking something that might exist but to my point of view is a straw man: The idea that “digital mind” (my term) researchers are trying to develop algorithms that simulate human minds – that is, actually write code that behaves like a mind. They ignore the approach that seems more reasonable to me, which is that the code is just a dumb physics simulation and the mind exists in the data it manipulates – ie a true uploaded mind, no code involved.

Inferno and Escape from Hell by Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle

I’ve never read Dante’s Inferno, but I gather it was a poem rather than a story so I probably would have found it frustrating anyway.

These two stories I quite enjoyed, but I tend to enjoy everything involving Niven, and his collaborations with Pournelle are always good.

What I take to be the main theme here is that the common image of Hell as a place of internal punishment just doesn’t make sense when you approach it rationally, but if you make the assumption that it’s not supposed to be eternal punishment but only sufficient punishment, then it becomes possible to make some sense of it and of some other Catholic doctrines.

The Transhumanist Wager by Zoltan Istvan

I picked up a signed copy of this from Zoltan himself when I went to hear him speak about his US Presidential platform a few months ago. Zoltan for President, by the way!

It’s a tour of transhumanist thought couched in an adventure story. It was a fun enough read, but there were some spots that could have used some editing and other forms of polish, and as stories go it was a bit lacking in suspense – the threats facing the protagonist just didn’t seem sufficiently credible to create drama.

I did like the philosophical stuff though – there are a few wonderful rants about what’s wrong with the world today. Basically the only part of the mindset presented by the book that I don’t agree with is the assertion that enemies of progress should be killed if they don’t get out of the way. I think people who don’t want to be a part of the future can be allowed to practice the old ways apart from mainstream society, like the Amish.

The Lurker at the Threshold by H.P. Lovecraft and August Derleth

A delightful full-length story that I wasn’t aware of until I spotted it in a used book store recently. Thoroughly enjoyed this one – it fits nicely into the neighborhood formed by The Dunwich Horror, The Shadow Over Innsmouth and The Whisperer in Darkness, while mostly avoiding those noxious fish-men and involving some of the more interesting horrors of Lovecraft’s mythos.

The Fox Woman & Other Stories by a. Merritt

Reading that last Lovecraft book left me with a desire for more old-style adventure writing, and lacking another HPL to read I turned to Merritt, who combines a slightly later style with imaginative semi-science-fiction.

The titular short story was good but had an unsatisfying ending – overall it read like the introduction to a novel-length tale and felt unfinished.

Several of the other shorts in this collection were quite good. I quite liked The People of the Pit as it evoked some of the same atmosphere as The Metal Monster but with a touch of Lovecraft thrown in, and I really wish Merritt had been able to finish The White Road as it was an intriguing concept.

Linear Timelapse Robot v1

Just in case anyone is following me via RSS, I just posted a new static page about my latest electronics project, a prototype motion control robot for making timelapse movies.

End of the Roll

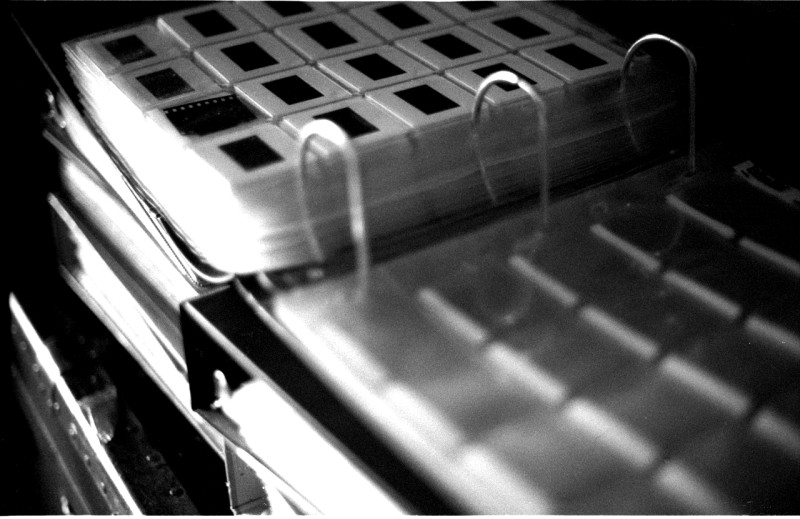

I just finished shooting and scanning my last rolls of photographic film. I’m done shooting film for the foreseeable future, and am going fully digital. Granted those last four rolls have been sitting unused in my fridge for six or seven years already, but their presence bothered me and now that they’re done I have some closure.

With those last rolls out of the way, I also have closure on a project that turned out to be much larger than I expected: Scanning all my film into the computer. In my approximately 32 years of shooting film I amassed 300 rolls, for a total of just over 9,000 images. That may seem tiny compared to what a typical professional film photographer would have, but it takes up to three hours to scan each roll. This scanning job has been done in bits and pieces of my spare time over the last ten years, but if I had been doing it as a full-time job it would have taken me four months!

I bought a dedicated film scanner (Nikon Super CoolScan 5000ED) for this purpose ten years ago, hoping that its batch scanning workflow would help automate the process so I could do other things at the same time. It did, but the scanner software is so flaky that most of the time I got to do other things in parallel just because of the length of time it took to scan each negative; on average I had to scan each film strip image about 1.5 times because of software glitches. Also the batch mode only works for film strips and half my film is mounted slides – but at least scanning individual frames did not expose as many bugs in the software as strips. I considered upgrading to a newer scanner for the latter half of the project, but there were not enough technology improvements to justify the expense.

Anyway, that’s all done now. What’s left is the almost as huge task of cataloging and tagging all my photos. I put a fair bit of effort into researching DAM (Digital Asset Management) software a few years ago and decided on idImager, which appears to have since been rebranded Photo Supreme, as it met more of my requirements for a better price than anything else I looked at. I’ve tried it and quite like it; the tagging and versioning workflow is great, it has some nice bonus features too.

For the record, my 9,000 scanned film photos take up just over 1TB of disk space – I’ve scanned them at 4,800 dpi or higher in 48-bit color, and they don’t compress well because of film grain and sensor noise. A typical image is 120MB big.

I’m really happy to have the scanning project over and done with. That was a lot of work.

This seems like a good time for a retrospective on my personal history with film and film cameras.

When I was a child my mother shot black and white on her Yashica-Mat TLR, and did her own darkroom work. She sometimes let me help with the developing and showed me how to play with the projector to make contact images of household objects and toys – I think that’s where my initial interest came from. It’s magic to shine a light on paper and have a permanent image appear.

—

Keystone 110

The first camera of my own was a generic pocket-sized 110 camera from Consumers Distributing. It had a built-in permanent flash, two focal lengths and a neat in-viewfinder flash ready indicator that I always wondered at the operation of – it was a clever design feature, lighting up despite having no light built in to the indicator. I shot a lot of what I now call tourist/documentary photos on this unit – that is, photos of interesting places and things, but with very little artistic merit to the photos themselves. I was too young to have developed a sense of what makes a photo great, though towards the end of this camera’s long tenure I started experimenting with composition and with panoramas made by taping prints together.

I also used a couple of disposable 110 cameras and one of those ultra-tiny kids’ “spy cameras” from the comic ads, which fits in the gap in the middle of the 110 cartridge.

Examples of pictures I took with the 110:

—

The Polaroid

Later I had a Polaroid instant camera. It was cool to get the photos immediately and the color and clarity were much better than on the 110, but the film was relatively expensive per photo and even as a child I recognized the value of having negatives available for reprints and enlargements. The Polaroid didn’t see frequent use because of its limitations, but it did last a long time.

Examples of pictures I took with the Polaroid:

The Bellows Camera

Also during my tweens I had an old-fashioned bellows camera. I believe it was a Kodak Tourist II given to me by my mother, based on her notes on her own photos. I didn’t use it much and it didn’t make much of an impression on my memory. Eventually the bellows got too many light-permitting punctures for the camera to work well, so I followed nature’s directive and took it apart to see how it was made.

Examples of pictures I took with the bellows camera:

—

The Pink Camera

My first 35mm camera was a cheap fixed-focus tourist model. This was basically the same deal as my 110 but 35mm instead. I no longer remember even what brand it was, but it look vaguely like this only pink. I got quite a bit of use out of it and started to develop a better sense of composition during this time (most of my teens).

Examples of pictures I took with the pink camera:

—

Pentax ESII

For my 20th birthday my parents gave my first “real” (read SLR) camera, a Pentax ESII with a fast 50mm prime lens. This is the film camera I got the most mileage out of, developing my artistic skill and eventually amassing a small collection of used lenses for it. When the electronics eventually failed I bought a second one to replace it, and that’s the camera I just finished shooting some of my last rolls with. I also picked up a Pentax Spotmatic, which uses the same lenses, so I could have two bodies for shoots where I would want to swap lenses a lot. For a while I did my own B&W developing at home too. The Pentax was an excellent, life-altering gift. The vast majority of my film was shot with it and most of my photographic learning was done with it.

Example ESII & Spotmatic photos:

The Crap Pentax

In the early 2000s I picked up a more modern Pentax, used, because I was curious to see what an auto-focus, auto-winding, zoom-lensed camera was like. Unfortunately this model was a bad choice, as it felt cheap and I didn`t like using it. I think I only shot one or two rolls with it, and I no longer remember which ones they were so no examples for this one.

—

The TLR

A few years ago my mother gave me her old Yashica-Mat TLR medium format camera, as she has also gone digital. In the end I only shot a few rolls with it though. It’s a nice camera but I’m put off by the lack of a built-in light meter.

Example TLR photos:

—–

I’m not saying I’ll never shoot film again; it has its applications. But digital is so much cheaper and more convenient and a good digital SLR produces pictures that seem as good, and as enlargeable, as what I shot with my 35mm SLR.

One thing that film does have going for it is its variety of grains and color treatments. Simulating the heavy grain of some B&W films or the weird color cast of cheap 110 film with digital images just doesn’t look the same – at best it evokes nostalgia for those things in those what grew up with them.

I give it twenty years before I develop a weird nostalgia for shooting film and dig out the old cameras.

HD44780 LCD Interface lib for Teensy++ 2.0

Just a quick post to announce that I’ve posted a new project page to the static part of my site: Teensy++ Interface Library for HD44780-Based LCDs

It’s about a recently completed electronics hobby project.

My Latest Profile Picture: What’s Inside

I’ve recently updated my social media profiles with a new profile picture / avatar, receiving positive response and some curiosity. This is the image, at a high resolution:

This is a picture of me wearing a picture of me. Read on to find out how this was done.

In 2010 the Electronic Arts Capture Lab had an open house, where employees from the rest of the studio could go by for demos of their equipment. See the video in the above link for examples of what we saw.

One thing they demonstrated was the facial capture rig they used to create high-resolution 3D models of actors’ faces. You can see the rig and part of the process between 0:09 and 0:17 in the video at the above link. It’s a rig containing a lot of digital cameras arranged spherically around the subject, and set up to fire in synchrony along with strategically placed flashes. Specialized software then takes all those photographs and correlates the features visible in them to deduce a textured, 3D digital model of the subject. This is one example of the science of photogrammetry. There is a longer discussion of this process in this thread post.

My colleague David Dixon and I had the idea to use these digitized models of our heads to construct actual physical models of our heads, at a larger-than-life scale, and wear them as Halloween costumes.

David, being the 3D editing wizard among the two of us, simplified the models from thousands of polygons down to dozens. Here are before (top) and after (bottom) screenshots of my model showing his work. Note the bottom one uses a corrected version of the skin texture (which I unfortunately lost the high-resolution version of) which explains the differences in skin tone and detail.

You can see the original model had quite a bit of surface noise to be cleaned up, including what looks like fractures in my cheeks but are probably registration errors.

We then imported the simplified model into Tamasoft PepaKura, which segmented it into flattenable pieces and added glue tabs, resulting in many pages of fragments that looked like this:

We had these printed on stiff paper at Staples, then spent hours gluing them together.

Here’s what mine looked like from a few angles the morning I finished it (I worked overnight to finish it in time):

And here are David and I showing them off at the office later that day:

For the profile picture image, I set up a mini studio in my apartment and had my visiting parents help me fit my suit jacket over the shoulders of the model (since I can’t see anything when I’m wearing it) and operate the camera for me. I then digitally emphasized the edges between the polygons and removed the background and replaced it, appropriately, with one of the iconic Max Headroom backgrounds.

So there you have it: A long, technical and involved but creative and fun project that lets me wear an oversized 3D photo of my head over top of my real head.